Mesozoic Monsters: a whole heap of vertebrate palaeontology, straight from the desk of researchers in the field. This is the title and tagline of my blog. I had every intention – when I started this blog – of regularly updating my readership with little titbits of my research, but I soon learned that it is not that simple and ideas need protecting and publishing first. So this is to be the first article that is submitted in the true spirit of MM.

The newly described Koumpiodontosuchus aprosdokiti Sweetman, Pedreira-Segade and Vidovic 2014 is a small crocodyliforme,

neosuchian, bernissartiid from the Isle of Wight, UK. The specimen was found a

couple years ago on the foreshore of Yaverland beach, Isle of Wight. The

associated sediment suggested that the material had come out of the Wessex

Formation, Wealden Group. The specimen, which is the holotype (type material)

and only specimen of Koumpiodontosuchus

is represented by a skull which was broken in two and found by separate

individuals, but they were married together by some “serendipity” (SCW in

Sweetman et al. 2014). I had the good fortune of working on this specimen, and

I was tasked with placing it in the crocodile evolutionary tree, which I will

discuss further below.

|

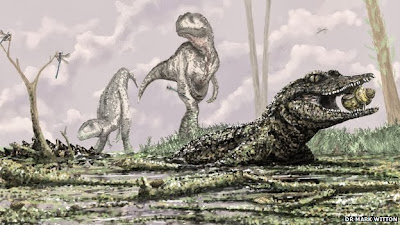

| A palaeontological reconstruction of the Wessex Fm. Biota, by Mark Witton, reproduced with his permission. |

Koumpiodontosuchus is a small crocodyliforme at an estimated

66cm in total length – the skull is 11.2cm in length. The dentition is

distinctive and alerted us to the natural affinities of this small croc. It has

a tribodont dentition in the distal portion of the jaw (back of mouth).

Tribodont teeth are bulbous, and kind of onion-shaped. Clearly these teeth are

involved more in digestion rather than prey capture. The mesial teeth (front)

are somewhat procumbent (forward pointing) simple cones, followed by some

pseudo-canine teeth, one of which projected up from the lower jaw and sat in a

notch in the side of the upper jaw, just behind the nares (nostrils). This

morphology is typical of a previously monotypic family (only contained one

genus), the Bernissartiidae Dollo, 1883. Thus, it would be expected that a

cladistic analysis would have no problem placing Koumpiodontosuchus with the type genus of the family Bernissartia fagesii “Known from

contemporaneous strata” (Sweetman et al. 2014) in Belgium and Spain. However,

there are some distinguishing features of Koumpiodontoshuchus

which are not only distinct from Bernissartia,

but also convergent upon Eusuchia. Namely, the position of a perforation named

the choana within the pterygoid bones, which is one of the defining characteristics

of Eusuchia.

|

| This image is made available by APP through the creative commons licence. Originally produced by UP-S & SCW in Sweetman et al. 2014. |

The specimen was first made public at SVPCA

Oxford, but at that time it became clear – in light of the above convergences –

that there were some unusual features this skull possessed which required

further exploration with cladistic methods, and so I was signed up – hence the

one and a half year hiatus.

The presence of compound characters in cladistic

analyses means that a systematist (someone who performs these analyses) may not

be telling the computer what they believe they are (Brazeau, 2011). As such

character conflict may be artificially high, causing some natural groups to

lack support, while other tentative groups gain support. Due to this and the

chimaera-like situation that Koumpiodontosuchus

found itself in meant that a whole new ‘Brazeau-acceptable’ analysis had to be

constructed, picking and choosing, or altering characters from published

analyses. So, in order to assess the systematic position of Koumpiodontosuchus an analysis coding 36

taxa for 242 characters was run in TNT, using a NT search. The result – after

running more procedures to find the maximum number of MPTs (most parsimonious

[best fitting] trees) – was a strict consensus of 17 trees with a length of 862

steps. A single tree was generated using implied weighting, which is the tree

we finally presented. The logic behind this is that implied weighting changes the

‘impact’ of conflicting characters whilst the analysis runs, thus diminishing

the effects of homoplasy (convergence of characters due to reasons other than a

natural affinity): perfect for this scenario. The result (see cladogram) was

that the Bernissartiidae was found as the sister-group to Rugosuchus, goniopholidids and Eusuchia. Interestingly,

Thalattosuchia – a major group of marine crocodiles (see my article on Dakosaurus) – was found within

Tethysuchia, a grouping that previously contained dyrosaurs and pholidosaurs,

exclusive of thalattosuchians. Worryingly, the presence of the choana within

the pterygoids of Koumpiodontosuchus,

and its placement outside of Eusuchia leaves the clade of ‘true crocodiles’

wanting a definition. Salisbury et al. (2006) were happy to define the clade

based on Isisfordia being the most

basal member of the family, but according to this analysis that would exclude a

lot of traditional Eusuchians. Brochu (1999) thought that Eusuchia could be

defined by the most recent common ancestor of Hylaeochampsa and Crocodylia, but this is also an unreliable

solution due to the shifting position of Hylaeochampsa

between many analyses.

| This image is made available by APP through the creative commons licence. Originally produced by SUV in Sweetman et al. 2014. |

| For any South Park fans. |

References

Brazeau, M. D. 2011. Problematic character

coding methods in morphology and their effects. Biological Journal of the

Linnean Society. 104: 489-498.

Brochu, C. A. 1999. Phylogenetics, taxonomy,

and historical biogeography of Alligatoroidea.

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 19 (sup. 2), 9–100.

Dollo, L. 1883. Premiere note sur les

crocodiliens de Bernissart. Bulletin de l’Institut Royal des Sciences

Naturelles de Belgique 2: 309–338.Salisbury et al. (2006)

Sweetman, S. C.,

Pedreira-Segade, U. and Vidovic, S.U. 2014. A new bernissartiid crocodyliform

from the Lower Cretaceous Wessex Formation (Wealden Group, Barremian) of the

Isle of Wight, southern England. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. Doixxx

No comments:

Post a Comment